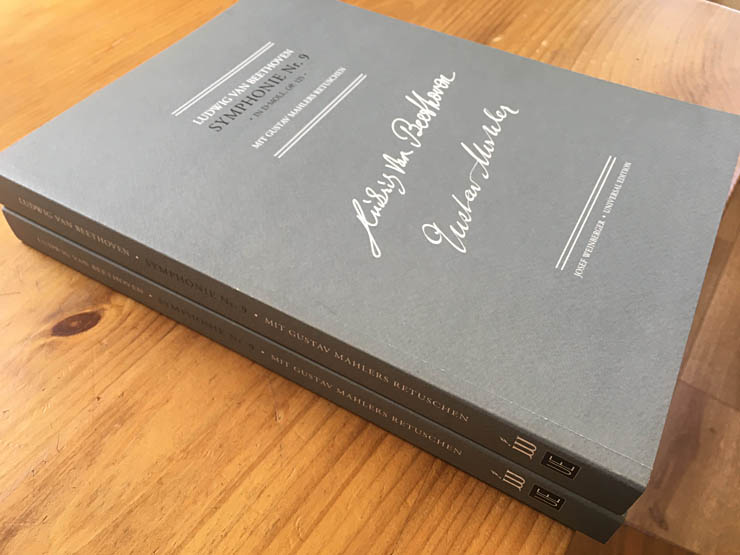

Gustav Mahler conducted Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on ten occasions: in Prague, Hamburg, Vienna, Strassburg and New York. For the last seven of these performances he prepared and used his own score and orchestral parts. I have transcribed and edited these materials...

A Personal History of Writing

I. From pen to computer

“How do I write?” “With difficulty!” is the common answer. But the difficulties have not always been caused by the same obstacles, and ignoring for the time being the problem of actually getting started on a document, which every writer faces at some point or another, I should like to consider the changes in the obstacles that I have encountered over the past few decades and the useful tools I have been able to commandeer.

In the days before I had a typewriter, I used to write everything sequentially in longhand, on every other line of a 10 x 8 pad. Then I would put my manuscript away for a week or more (assuming that I had allowed enough time for this) and return to it later to make revisions with red ink. In that second pass I often moved things around with large circles and arrows, and hieroglyphics that I would not understand a week later, and added pages called 3A, etc., restructuring, clarifying and polishing – not usually a very time-consuming process. And that was it. The final stage was to copy my draft out, in longhand for college assignments or, equally laboriously, with the typewriter later on when writing for HiFi News. I have always been a fast (and highly inaccurate) two-finger typist, and I used a lot of overstrikes with “xxx”, later refining the process with correction fluid. In those days, when one needed multiple copies one used sheets of carbon paper or cut a stencil for a duplicating machine, pounding the keys of the typewriter even harder than usual to ensure an impression with the nth carbon, or to cut through the wax of the stencil with the black and red ribbon safely disengaged.

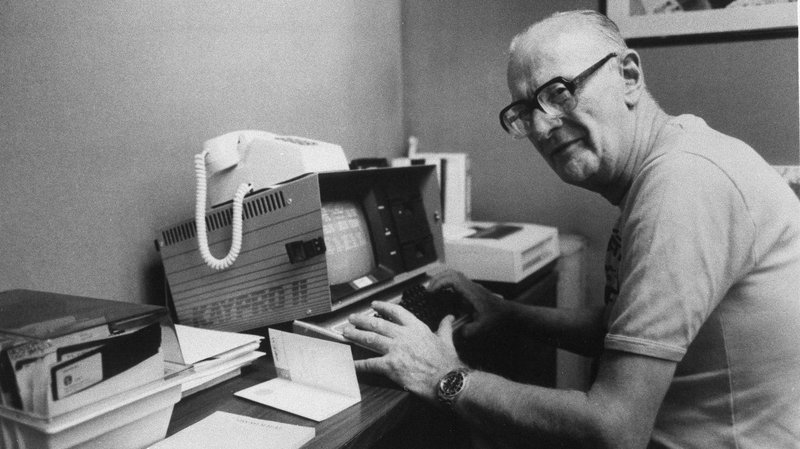

In 1985, after several unsuccessful attempts at writing on mainframe computer terminals, I bought my first computer, a Kaypro II.This computer served me well: I modified the hardware extensively, effectively making it into a Kaypro IV by adding double-sided diskettes (holding all of 390kB), increasing the clock rate from the standard 2.5 MHz to a whopping 7 MHz, and adding a 1 MB (!) RAM disk and MIDI ports. I also supercharged the CP/M software. I wrote my doctoral thesis using a heavily modified version of Perfect Writer (a version of EMACS) and Perfect Formatter, which divided the long vertical scroll of text into pages and applied the formatting codes that I had inserted by hand. This had to be followed by Perfect Printer, a program that sent the output of Perfect Formatter to the printer. The process was quite a challenge, but I was in good company: Arthur Clarke of 2001/2010 fame also wrote on a Kaypro.

Arthur Clarke at the Kaypro II

With the acquisition of a computer, my methods of working changed, and it took longer to produce a finished product. Pencils and pens are low maintenance items that can be replaced relatively cheaply, but computers need servicing, and this takes longer and costs more than sharpening a pencil. I now found myself spending hours reading the manuals, memorizing shortcut keys (Thankfully the Kaypro had no mouse, which taught me good habits.) and trying to make the word processor do what I wanted it to do.

When I write with a pen, I find that my thoughts outstrip my ability to notate the words: typing actually slows down my thinking to keep pace with my fingers. With the computer keyboard I can type faster. My thoughts keep pace, and I can ignore my “bum notes” and correct the typos later. As I am inclined to jumble up the letters in a word when I type, I greatly appreciated the EMACS commands CTL-t and ESC-t, which enabled me to transpose the order of two letters or two words respectively. As far as the composition was concerned, I used Perfect Writer to write snippets as they came to mind, and then shuffled the words, sentences and paragraphs around until I was happy, throwing away the text for which I had to admit I could not find any real use.

Now I had the opportunity of printing my work out and this meant the chance to write all over it in red ink (nostalgia kicked in!), and then correct, and then print and so on until I got fed up and decided to abandon all hope of making further improvements to my deathless prose. Despite the promise of a paperless office, a lot more trees are cut down to feed one’s writing habits with a computer. Apart from the mania for undisciplined and endless revision, one unfortunate phenomenon of looking at virtual paper on the computer screen is that simple errors do not jump out at you with the immediacy that they do on real paper.

My first printer was an indestructible Epson FX-80 that went to work gleefully with a noise reminiscent of a newspaper printing press in full cry. This was replaced by a Hewlett Packard DeskJet 600 printer. By comparison with the Epson this purred like a Rolls Royce. It also produced more elegant results, but it was slower than the Epson and had an intemperate thirst for ink that came in expensive cartridges – an addiction which for some reason had not been declared in the glossy brochure.

The Kaypro II

I will delay discussion of the computer that weaned me from the Kaypro, as there are still things to be said about the two “word processing” programs bundled with the Kaypro. (I use inverted commas because the term implies to me a distinctly industrial approach to writing.)

II. The friendly software

These programs were Perfect Writer (a version of EMACS) and Wordstar. Wordstar was like MS Word in that it was page oriented and it inserted invisible codes into the textflow that formatted the text onscreen. But in my experience Perfect Writer was far superior: it was elegant, lean, and better suited for my purposes. Wordstar was a word processor, good for writing letters to the editor, recipes, shopping lists and memos, whereas Perfect Writer was a text editor, and more useful for creating documents longer than a couple of pages – like my 600-page thesis.

What one saw on Perfect Writer’s screen was a document up to 70 characters wide without any page breaks, like a vertical scroll. The typeface was quite legible, but not even as glamorous as Courier. Unlike my typewriter, text was wrapped without any bell reminding me every so often that I needed to hit the carriage return; but the only onscreen formatting that was offered was the separation of paragraphs with a blank line, though inline visible codes could be inserted by hand to tell Perfect Formatter how to lay the text out when preparing it for printing.

Someone who has never used a Kaypro may be excused for thinking that its green 9-inch cathode ray tube was inadequate. It was not. It allowed 24 lines of 70 characters – about 1.5 kB of text, which is quite enough. The size of the documents was limited to the 390kB that could be fitted on a 5.25-inch floppy disk – again, quite an adequate amount. Simple and memorable commands scrolled the text up and down through the window with ease, or moved the cursor to the beginning of a word, sentence, line, paragraph or document. By splitting the screen display vertically, one could view either two different documents or two sections of the same document and move chunks of text of any size between the two windows. Virtual memory in the form of a swap file effectively extended the meagre 64kB of physical memory that the Z80 processor could address. Documents could be loaded onto the external RAM drive that I added, and this speeded up the editing process considerably, short of a power cut, requiring no floppy disk saves until the end of the session.

Lacking fancy formatting, the only feature that is noticeable onscreen is the quality of the writing itself. Because of this I still prefer not to compose text in Word, using a font that glamourises my prose, making it look as if it has been printed and bound by a master printer. Only when I am happy with it do I transfer my naked text to a program that uses the wiles and conceits of typesetting to display it to its best advantage. I like using a virtual typewriter for composition, appreciating the leanness of the process – the simple ability to read what one has actually written (if I were a spy by profession my handwriting would suffice to encrypt and protect eternally from the enemy any sensitive messages) – while allowing one later with minimal effort to convert the typescript to a font of one’s choosing in seconds.

I have tried writing methodically, but most of what I write has a structure that is sui generis, and that sometimes takes a lot of kneading to reveal itself. (This is about all I can claim to have in common with Beethoven.) Unlike, say, a report of a scientific experiment, where one writes in a prescribed manner and order – a description of the problem, the method of investigation, the results and the conclusion – I find it difficult to pour my thoughts into a preformed mould. Instead of a skeletal outline, I usually begin by developing my thoughts as separate chunks of text, in whatever order they occur. Printing these out and writing all over the paper (coloured inks are fun!) helps me to see how they relate to each other, the order they should follow and what is wanting or superfluous. Another advantage of the scroll-like presentation is that the length of the document is more readily dictated by the content rather than a specific physical layout on the page.

I continue to use EMACS in its Windows incarnation (GNU EMACS), for the very reasons described above, and regard my early encounter with one of its many offspring, the aptly named Perfect Writer, as highly fortuitous.

/more to follow...

last revised 17 June 2020