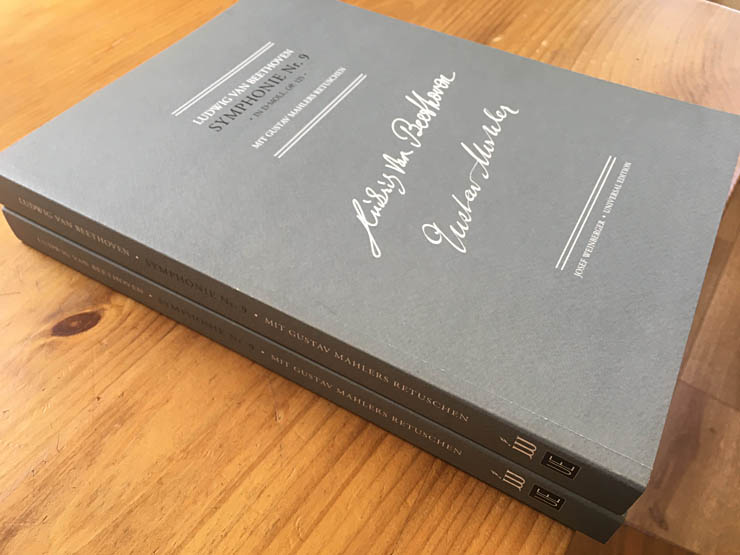

Gustav Mahler conducted Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on ten occasions: in Prague, Hamburg, Vienna, Strassburg and New York. For the last seven of these performances he prepared and used his own score and orchestral parts. I have transcribed and edited these materials...

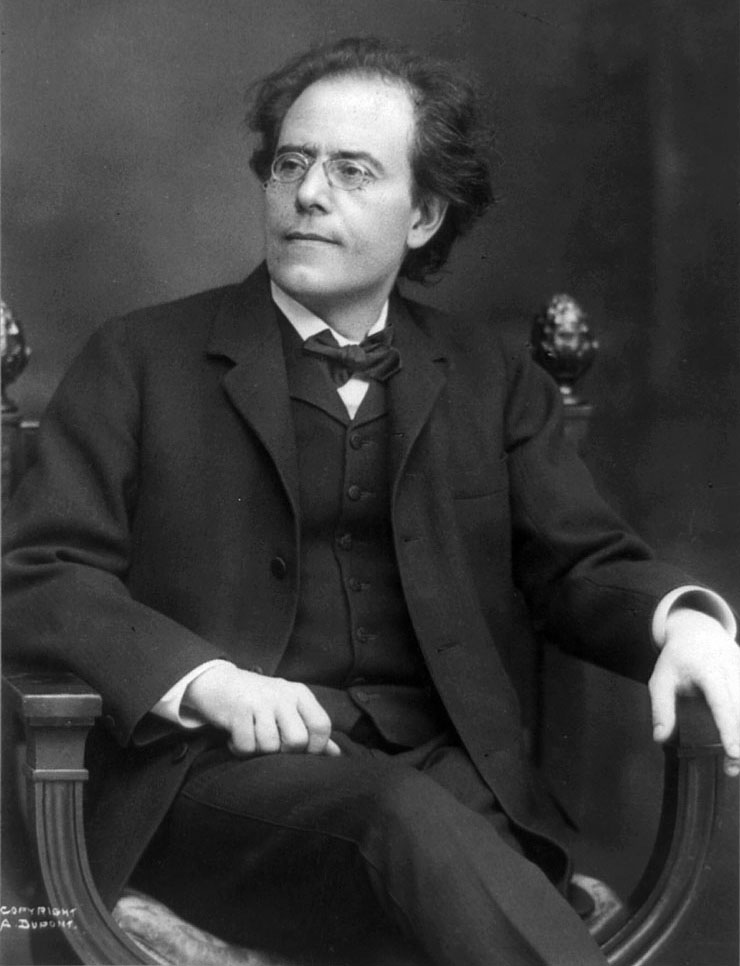

Orchestral Balance in Jascha Horenstein’s

Mahler Recordings

Jascha Horenstein is highly regarded as a Mahler interpreter. It is, therefore, particularly unfortunate that, with the exception of the recording made of the performance of the Eighth Symphony in the Albert Hall on 20 March 1959, his Mahler recordings were often compromised by a poor orchestral balance. Many microphones were placed close to individual instruments, and these can be heard so loudly in the recording that the natural balance of the ensemble is disturbed, giving a false impression of what Mahler wanted. I will illustrate here just one passage from the second movement of the recording of the Fourth Symphony, but the listener will find many other cases in Horenstein’s Mahler recordings.

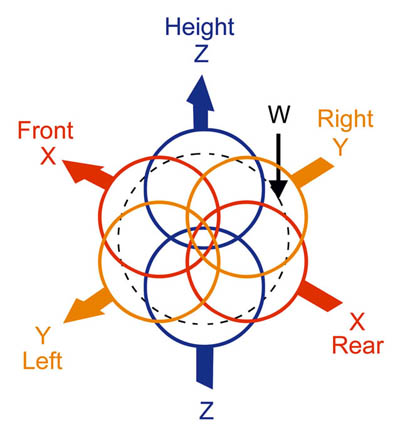

Transcription of the original ms of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony, 2nd mvt, bars 254-260

In Mahler’s manuscript the clarinets are marked mezzo forte, against the prevailing piano and pianissimo of the other instruments. By the time of the first published version of the score, Mahler had removed the second harp and reduced the level of the other instruments to pianissimo, leaving only the pizzicati of the violas and celli piano, with the clarinets now marked fortissimo.

It is characteristic of Mahler to indicate in his manuscript score the balance that he wanted to hear – in this case the clarinets a little louder (mezzo forte) than the pizzicati (piano), with the rest of the orchestra (pianissimo). Then later, often with the experience of hearing the work in rehearsal, he amended the written dynamics, giving the players the dynamics that they needed to play (fortissimo for the clarinets in this case), in order to produce the result he intended. If an instrument was not able to play loudly or softly enough to satisfy him, Mahler changed the instrumentation to provide the balance he needed.

Here we have a classic case of Mahler asking the clarinets, who sit at the back of the woodwind section, to play loudly in order to project their tone and prevent it from being swallowed up by the bodies of the other players around and in front of them. It seems that Mahler had to do this quite often with the clarinets when they were in a low register, and in his Retuschen of Beethoven and other composers he often raised the clarinets an octave in tuttis.

That Mahler’s clarinets often emerge too loud today, may indicate that the clarinet of his time was softer in the lower registers; but at all events, the clarinets sound too loud on Horenstein’s recording, actually appearing to be closer than the violins. This was achieved by raising the level of the microphone(s) close to the clarinets too much with respect to the overall balance of sound, such that one can hear the orchestra from two different perspectives at the same time.

Mahler: Symphony No. 4, 2nd. mvt, bars 254-266, London Philharmonic Orchestra / Jascha Horenstein, 1970

In the acoustic of the Barking Town Hall, where the recording was made, the close microphones may not even have been necessary; but more importantly, had the recording engineers and producer been able to read Mahler’s intentions from the score, this distortion of balance would not have occurred.

The above examples are expanded from David Pickett’s essay in the book Perspectives on Gustav Mahler, edited by Jeremy Barham and published by Ashgate Press, 2005.

Rev. 12 Dec 2018