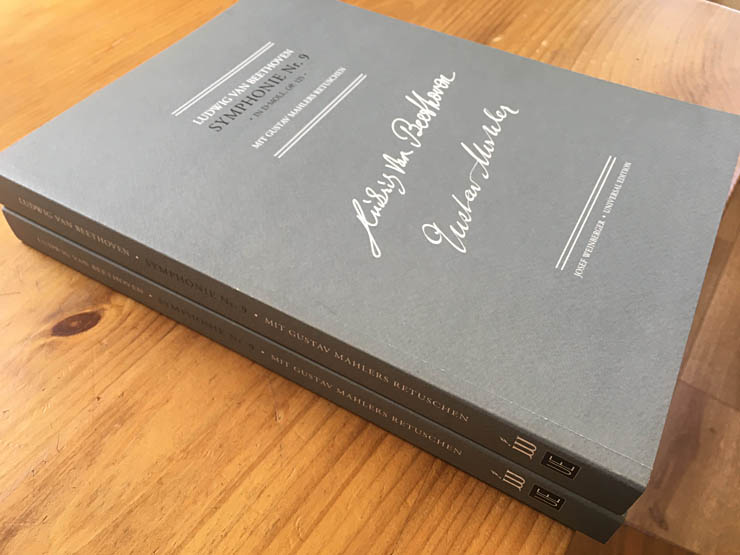

Gustav Mahler conducted Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on ten occasions: in Prague, Hamburg, Vienna, Strassburg and New York. For the last seven of these performances he prepared and used his own score and orchestral parts. I have transcribed and edited these materials...

Oskar Fried’s Recording of Mahler’s Second Symphony

As a conductor, Oskar Fried (1871 – 1941) was not a great technician; but he was highly devoted to the music of Mahler. It was at Mahler’s own suggestion that Fried conducted a performance of the Second (Resurrection) Symphony in Berlin on 8 November 1905. Mahler attended the dress rehearsal and, according to Otto Klemperer who was in charge of the off-stage band, gave Fried a last minute coaching in the tempi and style of the work between the rehearsal and the performance.

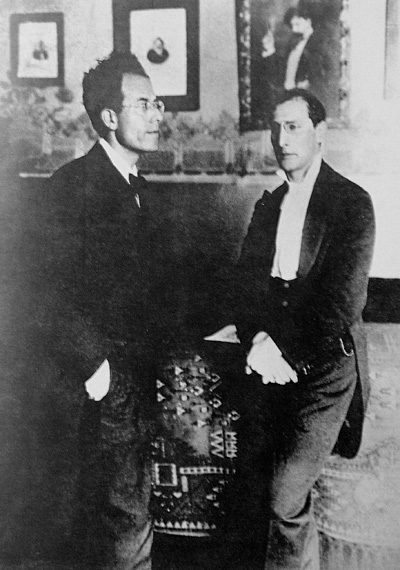

Mahler and Fried standing in front of a photo of Artur Nikisch, Berlin, 8 Nov. 1905

In 1923 or 1924, Fried made the first recording of this, or any Mahler symphony. This was an extremely ambitious undertaking for an acoustic recording – and considering its significance, it is very odd that the actual date is not known! Not only was the recording made entirely without the benefit of microphones, but at 83 minutes it was also the longest piece of music to have been recorded up to that time. Despite the natural limitations of acoustic recording, it is highly successful and can only have been achieved by means of careful planning and experimentation.

Balance is generally satisfactory, with the exception of a couple of places in the first movement, such as the oboe at bar 131, and the flute and solo violin in bars 217 – 221. As is normal for acoustic recordings, the tuba can sometimes be heard helping out the bassline and the percussion instruments are the most compromised. While the timpani sound good and are well tuned, the cymbals, when audible, sound more like a slapstick. In the Scherzo, the Ruthe (a birch brush used to tap the rim of the bass drum) clearly had to be brought close to the recording horn, and the triangle was replaced by pitched tubular bells that in places are startlingly loud.

In making the first-ever recording of a Mahler symphony, Fried must surely have tried to follow the detailed advice that Mahler gave him about it nearly twenty years earlier. Several features of the interpretation point to this, of which I give two examples here.

A Rarely-observed Tempo Direction

Fried is the only conductor that I have heard on recordings who follows Mahler’s instructions to the letter at bar 235 of the first movement (Immer noch etwas vorwärts — always pressing forward ). Other conductors stay in tempo from this point for the next eight bars, whereas Fried rushes headlong into the abyss, fully justifying the climax and disintegration that follow.

The tempo at the beginning of this extract is approximately M.M. 72 for the minim (half-note). By the end of the passage Fried has reached approximately M.M. 108 — an increase of 50%.

Mahler II, 1st mvt, bars 221 – 250, Orchester der Staats-Oper, Berlin / Oskar Fried, 1923 or 1924

Soprano or Contralto?

It is clear that Fried assigns bars 601 – 611 of the finale to the contralto, rather than the soprano specified in the score, obviously recalling that Mahler had written to him before the latter’s Berlin concert: “I always have this passage sung by the soloist whose voice is best suited to the music...” After the contralto entry in bars 560 – 587 (O glaube, mein Herz), there is a brief interlude and the next entry (O glaube: Du wardst nicht umsonst geboren!) is clearly sung by the same singer (Emmi Leisner).

Mahler II, 5th mvt, bars 560 – 611, Emmi Leisner (alto), Orchester der Staats-Oper, Berlin / Oskar Fried, 1923 or 1924

The above examples are expanded from my essay in the book Perspectives on Gustav Mahler, edited by Jeremy Barham and published by Ashgate Press, 2005.

Rev. 12 Dec 2018